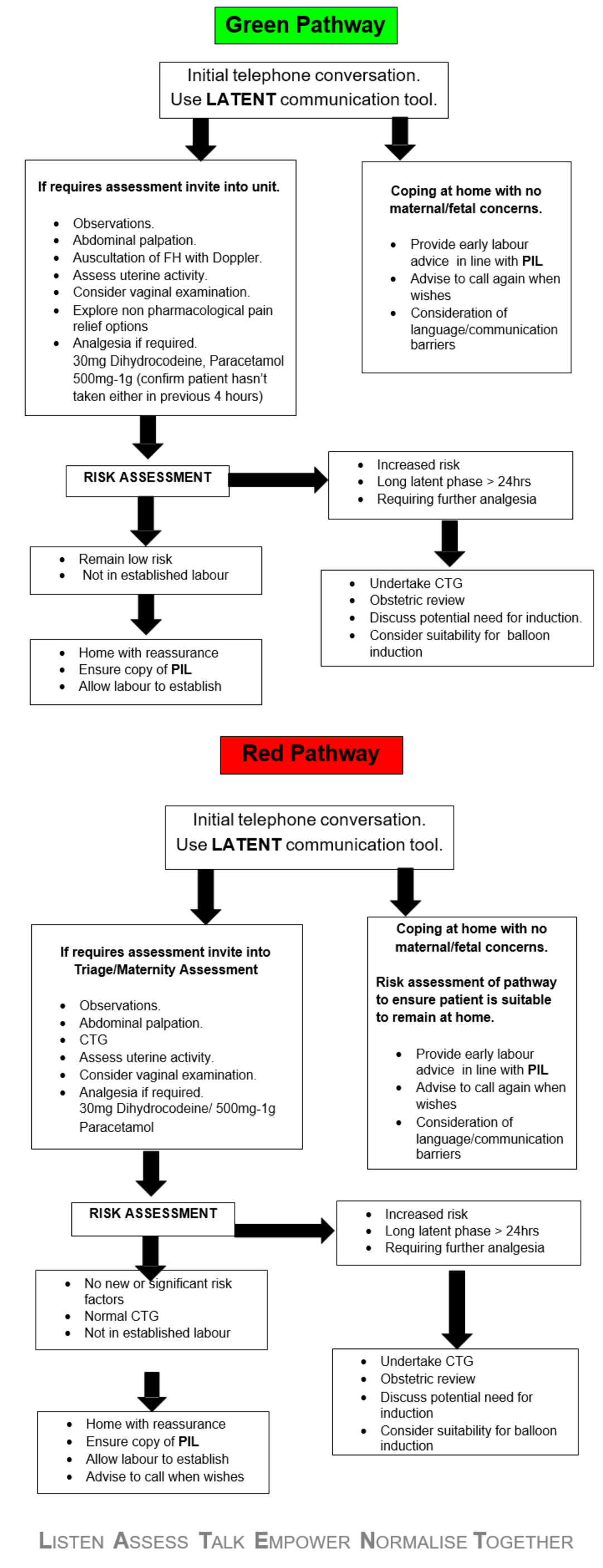

Managing the latent phase of labour is without doubt a challenging time for both women and midwives’ alike. Whilst we know that labour happens in stages it is important to remember that there is no such thing as a typical labour or birth – each woman’s experience will be individual and different as will their plan of care. The requirement of support for each woman throughout the latent phase will inevitably be unique and require a person centred, holistic approach.

NICE (2014) defines the latent phase of labour as - a period of time, not necessarily continuous, when there are painful contractions with cervical change. Including cervical effacement and dilatation up to 4 cm.

Most often the first episode of care in early labour will be sought from Triage/Maternity Assessment, whereby women are seeking support and advice via telephone. In this instance communication is key. The RCOG identified a recommendation in their Safer Childbirth (2007) publication, whereby there is a need to improve communication between healthcare professionals and women. Each care provider should foster a team approach based upon mutual respect, a shared philosophy of care and transparent lines of communication.

Midwives are tasked with disseminating large volumes of information to women they care for. The process of education and information sharing, aids women’s decision making, increases their confidence and ultimately enables them to feel empowered. Maxwell (2019) refers to this as “The Midwife Effect”, where midwives have the inherent ability to empower women physically, psychologically and socially. There are 2 defining attributes in the empowerment of women in childbirth - a woman’s belief in herself and a meaningful interconnectedness with carers (Niewehuisze and Warren 2019).